The Right Excellent Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jamaica’s first National Hero, once leader of the largest organised mass movement of African people, the man who inspired every black freedom fighter in the twentieth century, both in Africa and the Americas.

He left a legacy, inspiring great humans like Martin Luther King, Bob Marley, Mohammed Ali, Walter Rodney, Mahatma Gandhi, Minister Louis Farrakhan, President Nnamdi Azikiwe, Elijah Muhammad, President Kwame Nkrumah, Kwame Toure, President Jomo Kenyatta, President Nelson Mandela, President Patrice Lumumba, President Julius Nyerere, Malcolm X amongst many others but was disregarded in his country of birth.

All the same, given the anxiety in some quarters about the African heritage in Jamaica, it is truly remarkable that the political elite had the good sense to recognise Garvey’s heroic stature and honour him accordingly.

Born on August 17, 1887, only 21 years after the Morant Bay rebellion, and 53 years after Emancipation, Garvey grew up in a Jamaica that was still trapped in psychological bondage. As a child, he would probably have heard the denigrating mantra, ‘Nutten black no good’. He might even have been asked, ‘How yu so black an ugly?’ As if he had anything to do with it.

Garvey grandly rose above the hateful definitions of blackness in Jamaican society and prophetically affirmed, “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind”. Many of us sing along with Bob Marley, who popularised Garvey’s words in his “Redemption Song”. But do we fully comprehend the profundity of the exhortation to free the mind?

Garvey made that liberating statement in 1937 at a meeting in Halifax, Nova Scotia. By then, he was almost at the end of his tumultuous life. He died less than three years later in London. Like many Caribbean migrants of his day, Garvey caught the spirit of exploration. He went to Central America when he was twenty-three, then to the UK, returning home in 1914.

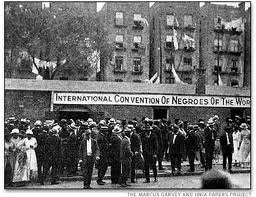

In August that year, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Jamaica. He went to the U.S. in 1916, and by 1917 had launched the New York Division of the UNIA with all of 13 members. After three months, there were 3500 dues-paying members!

‘The Moses of the Negro Race’

Without access to Facebook and Twitter, the UNIA grew exponentially. Almost one thousand UNIA divisions were established within seven years. Garvey was soon described in messianic terms. The headline of a 1920 article published in the New York World loudly and, perhaps sceptically, proclaimed: “The Moses of the Negro Race Has Come to New York and Heads a Universal Organization Already Numbering 2,000,000 Which is About to Elect a High Potentate and Dreams of Reviving the Glories of Ancient Ethiopia”.

At the heart of Garvey’s vision of a universal movement of black people committed to self-improvement was the expectation that the colonised African continent would be liberated. Garvey asked himself some unsettling questions: “Where is the black man’s government? Where is his King and his kingdom? Where is his President, his ambassador, his country, his men of big affairs?” His answer: “I could not find them and then I declared, ‘I will help to make them.’”

You have to admire Garvey’s nerve. A lesser man might have quailed at the prospect of taking on such a superhuman mission. At the beginning of the twentieth-century, there were only two independent African countries: Ethiopia and Liberia. The rest of the continent had been captured by European squatters. Lion-hearted Garvey, girded with his philosophy of African Fundamentalism, militantly declared, “Africa for Africans, at home and abroad.”

Garvey saw parallels with the struggles of other oppressed groups who were demanding the right to self-government. In a speech delivered at Liberty Hall in New York in 1920, Garvey related why he’d started his career as a street preacher, spreading the good news of African redemption: “Just at that time, other races were engaged in seeing their cause through—the Jews through their Zionist movement and the Irish through their Irish movement—and I decided that, cost what it might, I would make this a favorable time to see the Negro’s interest through.”

“The Place Next To Hell”

Despite the global reach of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, and his overarching vision of economic enterprise, his wings were clipped when he was arrested on bogus charges of using the mail to defraud. Imprisoned, he took flight, writing The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, with the sustained editorial oversight of his second wife, Amy Jacques.

Despite the global reach of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, and his overarching vision of economic enterprise, his wings were clipped when he was arrested on bogus charges of using the mail to defraud. Imprisoned, he took flight, writing The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, with the sustained editorial oversight of his second wife, Amy Jacques.

Deported in 1927, the indomitable Garvey launched a newspaper, The Blackman (1929-1931), then The New Jamaican (1932-1933). Perhaps Jamaica wasn’t ready for the black man. In his first editorial, for The New Jamaican, Garvey spoke the plain truth: “Jamaica is a fine country from a natural viewpoint—it is a terrible country from economic observations. To consider how the people of Jamaica live, that is, the bulk of the population, is to wonder if we, at all, have any system of economics. We shall endeavour to enlighten the country on the possibility of creating a better order of things for everybody through a system of education in economics—a thing not generally known nor taught in Jamaica.”

Eighty years later, things have not changed ‘to dat’, despite political independence. We still haven’t gotten the economics right. In frustration with Jamaican politics, Garvey once described the island in an issue of The New Jamaican as “the place next to hell”. Despite the almost hellish circumstances in which he sometimes found himself, Garvey was always self-assured. An article published in The Daily Gleaner on January 19, 1935, quotes Garvey: “My garb is Scotch, my name is Irish, my blood is African, and my training is half American and half English, and I think that with that tradition I can take care of myself”.